An Example of Doing Learner Introductions in an Online Class

Getting coherent, complete, and thoughtful learner introductions in an online class requires intentional prompting and guidance.

By Joanna Bartell and Autar Kaw

September 2, 2020

Whether we are teaching online, face-to-face, or somewhere in between, having students introduce themselves is essential to the community building process for a class. When students know something about other students, it is easier for students to communicate with each other as well as with the instructor.

I have been teaching a core lecture class in Numerical Methods for three decades now. Although I am well-versed in several pedagogies, including hybrid, blended, and flipped learning, Numerical Methods had never been taught entirely online before the Summer 2020 semester. I come to know students by remembering their names, asking for their name when a student asks questions, or while conducting in-class active learning exercises in a flipped classroom.

In summer 2020, because of the COVID19 crisis, I had to teach the course online. I chose to give the “learner introduction” assignment to students to get to know them better as well to get students to know their peers.

The prompt of the assignment read as follows.

Since Jed and I have introduced ourselves, we would like you to do the same now by the end of the first week of classes. It will make it easier to communicate with you and your classmates. Say something about yourself (nothing personal), and what you expect from the course. About 50-100 words would be sufficient.

and the grading rubric was as follows.

You already have two samples of introduction, and you are not asked to give a lengthy introduction. 5 points for a reasonable introduction 2.5 points for less than a reasonable introduction. 0 points for an irrelevant introduction.

Although all students participated in this low stakes assignment (about 0.25% points), several responses were rich and gave an extended introduction full of anecdotes, but many of them were not uniform, lacked coherency, and some used instant messaging dialect and included several spelling and grammar mistakes.

Dr. Joanna Bartell is an instructor of Communication in the College of Engineering (CoE) at the University of South Florida, working to develop the CoE’s integrated communication program. Before joining the CoE in 2018, Dr. Bartell taught core communication courses for over a decade, including Interpersonal Communication and Persuasion courses. She is also well-versed in several pedagogies, including writing center and feminist pedagogy, which take highly individual, student-centered approaches. Who better to ask than Joanna about what can be done to elicit a better response from students.

I contacted Joanna, and she shared some of her experiences and suggestions, which she has outlined below:

Consider your request:

The learner introduction is a situating assignment, where you’re asking students to 1) talk a little bit about themselves, and 2) both understand and articulate their expectations. These are significant assignments and can help students understand and manage their expectations and involvement in the class. The reciprocity mechanism you include at the beginning of the prompt is helpful (“We opened up, now it’s your turn”) for getting students to respond to and mimic your introductory offering.

In your learner introduction assignment, students are asked to answer the following:

-

-

- Who are you?

- What do you expect from this course?

-

The rest of the assignment should be based on this request and what you hope students will gain from it.

Know your desired length and word count thresholds:

In my experience, while most students excel at writing as few words as possible, they’re not generally very good at getting the necessary information into those few words – concise writing is a skill that takes practice. Sentence lengths vary, with very long, complex sentences using up to 80 words (possibly more, but not typically), and very short sentences using as few as three words (e.g., “The dog ran.”), so knowing what you want from your students is key to writing the prompt.

For a skilled, concise writer, an adequate answer to the learner introduction prompts will probably be a minimum of 3 full-length, descriptive sentences (~20-25 words each), while an average writer will need more.

Define your preferred boundaries:

Most students like defined boundaries, which I have to balance with my desire to let students interpret clear assignment instructions and respond thoughtfully and creatively. Engineering students in particular, really want word counts. I find a balance between my pedagogical approach and students’ desires for rigid boundaries by locating a reasonable minimum threshold, as described above, and then doubling it (or more). This balance of expectations communicates to students that there is a general range for an acceptable response, but that they have agency and independence in how they respond. In my experience, this approach seems to satisfy students’ needs for boundaries and makes them feel more comfortable to connect and engage in a way that suits them.

In your learner introduction prompt, the instructors’ introductions model style and boundaries.

Define the audience:

This isn’t always necessary, but for assignments like this learner introduction assignment, I like to remind students that their writing is going to be seen by an audience of their peers. To take this a step further, I like to define what “an audience of their peers” is, exactly, and what kind of expectations that the audience has.

This is the prompt structure and wording that Joanna suggested, which we used for the class this Fall:

Rafael, Nicole, and I introduced ourselves, and we would like all of you to do the same. Introducing yourselves to us and your classmates will make communicating with one another easier. As part of your introduction, include the following: W [e.g., "where you're from," or, for distance learning, "where you're living right now"] X [e.g., "your field of study"] Y [e.g., "your desired profession after graduation"] Z [e.g., "your favorite pastime or hobby"] Your introduction must be clear, organized, and professional; you are introducing yourselves to learning colleagues who expect appropriate professionalism and personal engagement. Write 75-125 words or more.

About the rubrics, Joanna suggested defining the rubric points a little more. She noted that she prefers to grade assignments like the learner introduction assignment using the general notions of “thoughtful and complete.”

The existing rubric point of “a reasonable introduction” is highly debatable and may signal to students that this assignment is low expectations and low stakes. Although it might not be particularly high stakes, I like to use early assignments to set expectations for students that, even in low stakes assignments, students are expected to meaningfully engage in the course content, tasks, and assignments.

The grading rubric we used was as follows: You already have three samples of introduction, and you are not asked to give a lengthy introduction. 10 points for a clear, organized, and professional introduction. 5 points for mostly missing one of the above three requirements. 0 points for mostly missing two or more of the above three requirements.

So I tried it in the Fall 2020 semester, and I noticed that almost all the learner introductions were coherent, complete, and had anecdotal components.

This semester, I left voice feedback for all the learner introductions. Many students were pleasantly surprised and thanked me for the feedback on possible courses to take and career paths to explore.

It may be “small stuff,” but it is the accumulation of “small stuff” that makes up the quality of the classroom environment.

Mobile Preview

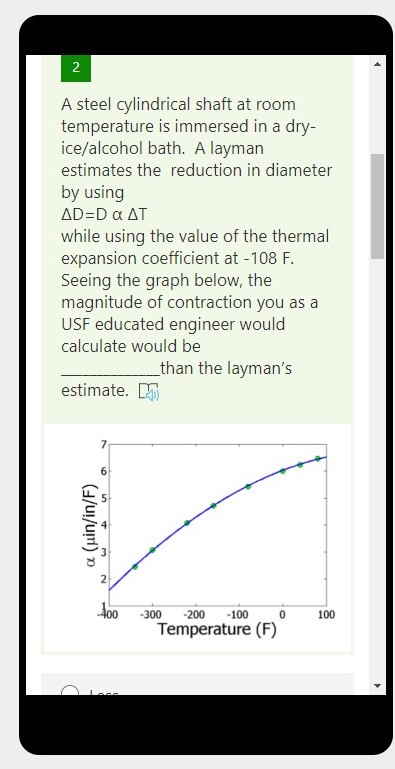

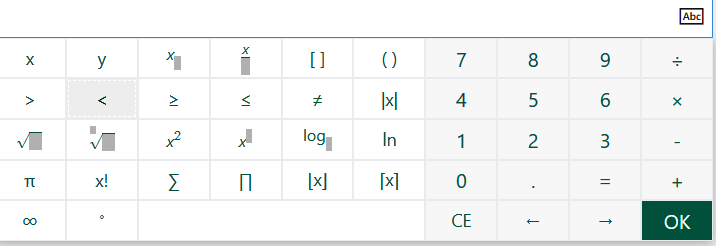

Mobile Preview Equation Pallete

Equation Pallete

Share Options

Share Options QR Code

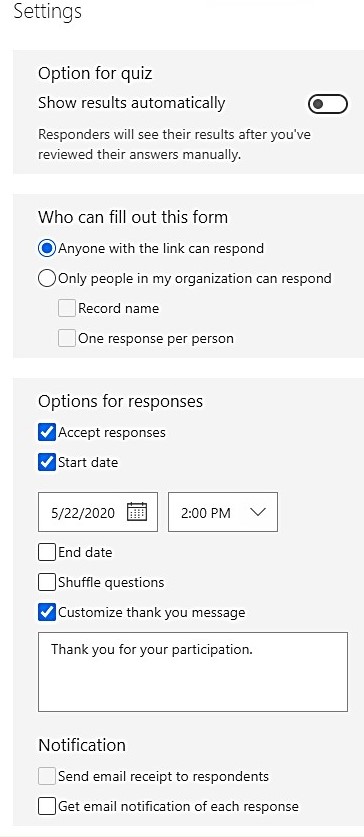

QR Code Settings

Settings